This year I’ve been working on my Master’s dissertation in the area of Bayesian Deep Learning. The focus of the project has been on developing a new method for generating counterfactual explanations — explanations that tell us what minimal changes to an input would have led a model to make a different decision.

In this post, I’ll give an overview of the background to the problem, the method I’ve proposed, and the main motivations that shaped the design.

Background

Counterfactual explanations are one of the most widely used approaches in Explainable AI. If a classifier denies you a loan, a counterfactual might tell you: if your income was €10,000 higher, the model would have approved you. These kinds of explanations are useful because they are both interpretable and actionable.

The challenge lies in generating counterfactuals that are realistic. Most existing methods rely on a generative model (like a VAE) trained alongside the classifier. The input is mapped into the generative model’s latent space, and optimisation steps are taken in this space until the classifier changes its decision. While this can produce realistic counterfactuals, there’s a fundamental misalignment: the generative model’s latent space is learned in an unsupervised way and may not correspond to how the classifier actually makes decisions.

Proposed Method

This project explores a different approach: instead of relying on a separate generative model’s latent space, can we generate counterfactuals directly from the classifier’s own internal representations?

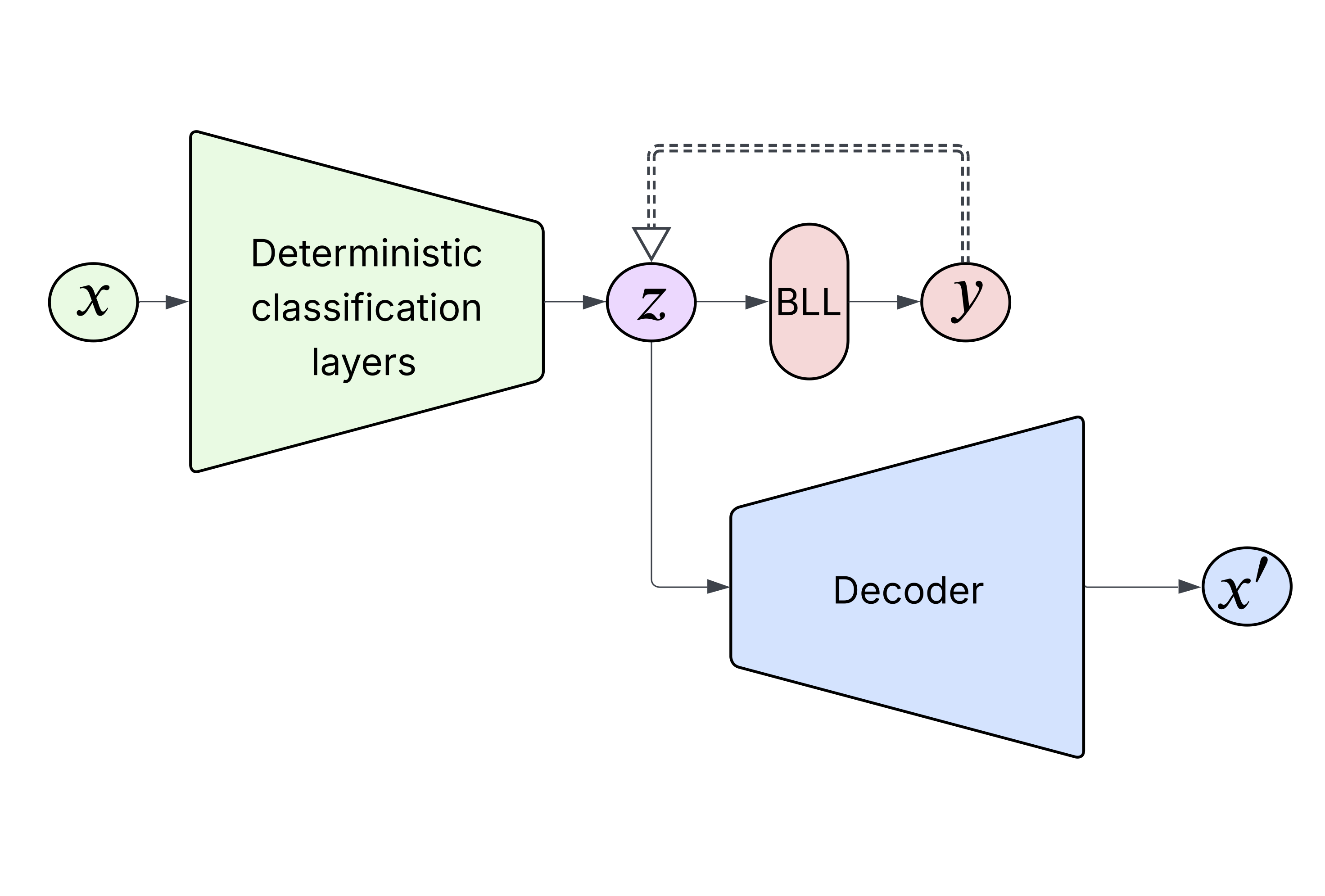

The method proceeds in three stages:

-

Embed the input: pass the input through the classifier up to the penultimate layer to obtain its latent representation.

-

Optimise in latent space: perturb this representation using gradient-based optimisation so that the Bayesian last layer predicts a different target class, while keeping the perturbation minimal.

-

Decode back to input: use a decoder trained on penultimate embeddings to map the counterfactual representation back into the input space.

The key insight is that the penultimate layer of a classifier defines a discriminative feature space—one where the model has already learned to organise data according to the classification task. By searching for counterfactuals in this space, we should find explanations that are more aligned with how the model actually makes decisions.

Crucially, this approach uses a Bayesian last-layer neural network—a hybrid architecture where the network is trained normally up to its penultimate layer, but the final classification layer is Bayesian. Unlike standard neural networks that learn single point estimates of their weights, Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) learn probability distributions over weights, providing principled uncertainty estimates.

Why This Bayesian Approach?

Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) provide several advantages for counterfactual generation:

-

Calibrated uncertainty: BNNs provide principled measures of both epistemic (model) and aleatoric (data) uncertainty, helping us avoid counterfactuals that lie in ambiguous regions near decision boundaries.

-

Adversarial robustness: BNNs have been shown to be more robust to adversarial attacks, making them less likely to produce unrealistic counterfactuals that exploit model vulnerabilities.

-

Out-of-distribution detection: BNNs naturally express low confidence for inputs unlike those seen during training, helping ensure counterfactuals remain realistic.

Training a full BNN is computationally expensive, so Bayesian last-layer neural networks (BLLs) are often used as a compromise—offering Bayesian inference at much lower computational cost. This architecture is particularly well-suited to our approach: by concentrating all uncertainty quantification in the final layer, we can optimise the penultimate embeddings using gradients from the Bayesian layer without losing the principled uncertainty estimates. The Bayesian last layer provides uncertainty-guided gradients that keep our counterfactual search realistic and well-calibrated.

Motivations

The design of the method was guided by four main motivations:

1. A discriminative space for counterfactuals

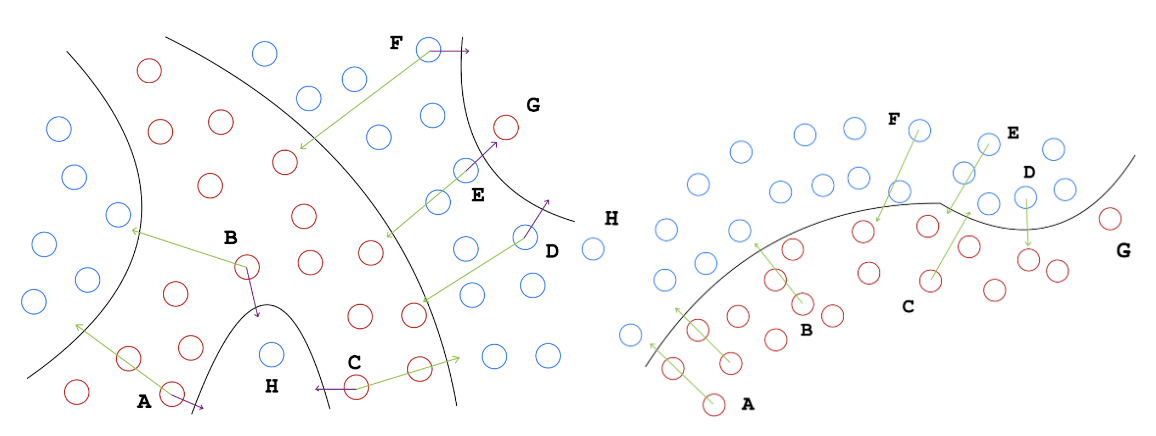

Most existing work uses the latent space of a generative model to approximate the data manifold. However, these spaces are unsupervised and not necessarily aligned with the classifier’s decision boundary. Bodria (2023) provides a key insight: the latent space used for counterfactual search should be discriminative, organising data so that instances with the same prediction are close together. As illustrated below, such spaces yield counterfactuals that explain the global decision boundary rather than identifying nearby outliers or adversarial examples. While conditional generative models could inject label information, we instead leverage the classifier’s own discriminative latent space at the penultimate layer, where class structure and prototypes are already encoded.

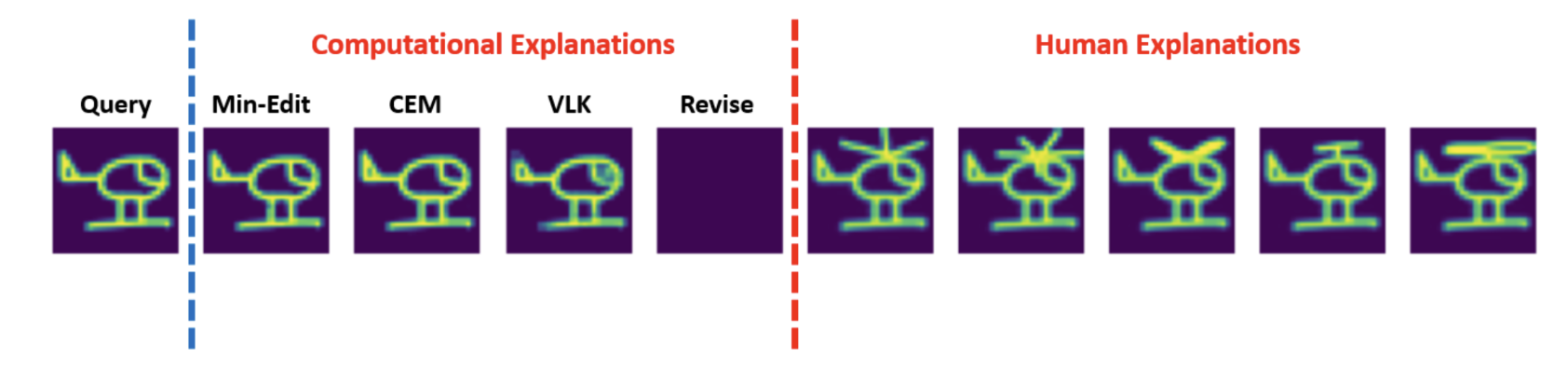

2. Human counterfactuals and similarity

Studies by Delaney et al. comparing human- and machine-generated counterfactuals show that humans tend to make larger, more semantic edits that move inputs closer to prototypes of the target class. This may align with the structure of the penultimate layer: Seo et al. theorise that the final layer’s weights represent class prototypes, serving as mean directions for the von Mises-Fisher distribution of penultimate activations. If this theoretical framework holds, then distances in the penultimate space could correspond more closely to human notions of similarity than distances in input space, potentially yielding more prototypical counterfactuals as recommended by human studies.

3. Bayesian last-layer robustness

One risk when perturbing latent representations is that counterfactuals might drift into unrealistic or adversarial regions. The Bayesian last-layer architecture addresses this directly: since all uncertainty estimation is concentrated in the final layer, we can perturb penultimate embeddings while preserving the strong uncertainty quantification of the Bayesian layer. Bayesian neural networks provide intrinsic adversarial robustness and show low confidence for out-of-distribution examples, making them well-suited for counterfactual generation. During optimisation, the Bayesian last layer’s gradients should guide the search towards realistic, in-distribution embeddings while remaining robust to adversarial perturbations in the embedding space.

4. Computational efficiency

Generative-model-based approaches require multiple forward passes through both the classifier and the decoder for every optimisation step. As illustrated below, the gradient path from prediction back to the latent representation must traverse the entire classifier plus decoder at each step. By contrast, in this method the optimisation takes place entirely within the penultimate embedding, with gradients only passing through the single Bayesian last layer to reach the latent space. The decoder is only used once at the end to map the counterfactual back into input space. This means that as classifier or decoder complexity grows, the core optimisation loop’s complexity remains constant, making the method highly scalable.

Results

Initial experiments demonstrate that this approach successfully generates meaningful counterfactual explanations. The results reveal two key advantages of the Bayesian approach: counterfactuals avoid adversarial behavior and show improved gradient reliability during optimization.

Non-Adversarial, Meaningful Changes

The counterfactuals generated by the Bayesian last-layer model make clear, interpretable changes rather than imperceptible adversarial perturbations. When tasked with changing a handwritten ‘9’ to an ‘8’, the Bayesian model hollowed out the upper loop and introduced a lower loop—changes that genuinely make the digit resemble an ‘8’. In contrast, the deterministic model made virtually imperceptible pixel-level changes that, while technically successful, exploit the model’s vulnerabilities rather than explaining its genuine decision-making process.

This difference reflects the Bayesian model’s principled uncertainty estimates. Rather than making confident predictions in ambiguous regions near decision boundaries, the Bayesian approach requires optimization to cross decision boundaries with greater margin, resulting in more substantial and interpretable changes.

Gradient Reliability and Optimization Stability

The Bayesian approach shows dramatically improved optimization reliability. In tests across 50 ambiguous examples, the deterministic model’s optimization failed 42% of the time, while the Bayesian model never failed to converge. This difference stems from the gradient information available during optimization.

Analysis of the prediction gradients reveals that deterministic models create sharp decision boundaries with plateau regions where gradients approach zero. This causes the “plateau effect”—optimization makes no progress until it suddenly jumps across the decision boundary, if at all. The Bayesian model’s smooth, probabilistic decision boundaries provide consistent gradient information throughout the latent space, enabling reliable gradient-based optimization even in highly discriminative feature spaces.

These findings suggest that Bayesian uncertainty estimation not only improves the interpretability of counterfactuals but also makes gradient-based optimization fundamentally more reliable in discriminative latent spaces.

Future Work

This work opens several promising directions for future research, particularly in areas where gradient-based optimization in latent spaces faces similar challenges to those addressed here.

Language Model Steering and Intervention

At a fundamental level, this work focuses on intervening in the internal representations of a deep classifier to change its output. This directly relates to the problem of steering large language models (LLMs), where the goal is to control their behavior using interventions in their latent space. For example, detoxifying LLM outputs can be framed as a counterfactual problem: what needs to change such that this toxic output is classified as non-toxic?

Recent work on “Steered Generation via Gradient Descent on Sparse Features” uses Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) to learn disentangled representations of LLM internal features before performing gradient-descent optimization to guide features towards target classes. This approach shares striking similarities with our work, using prototypical network classifiers where log probability is given by distance to target class prototypes.

Future work could consider replacing these simple classifiers with Bayesian neural networks, motivated by our findings on gradient reliability and in-distribution optimization. The smooth decision boundaries of Bayesian classifiers could enable more reliable steering interventions, particularly when moving between semantically distant concepts where traditional methods might encounter plateau regions with poor gradient information.

Bayesian Fine-Tuning of Internal Representations

During the development of this work, I experimented with an additional training step that didn’t make it into the final results but may be worth exploring further. The idea involves “fine-tuning” the deterministic layers after training the Bayesian last layer.

The standard approach trains a Bayesian layer on top of a pre-trained deterministic backbone. My experiment added a third step: freeze the trained Bayesian layer and continue training the earlier layers to maximize prediction accuracy given the probabilistic final layer. The intuition was that by sampling from the Bayesian posterior at each training step, the deterministic layers would learn to provide more robust and smoothly distributed representations.

I implemented this concept (available in the project code under ‘/training_notebooks/finetune_backbone.ipynb’), but initial experiments didn’t show major improvements for counterfactual generation, so I focused elsewhere. However, as far as I’m aware, this approach hasn’t been discussed broadly in the literature and could be a fruitful area for future work.

The theoretical motivation is compelling: given Seo et al.’s framework showing that penultimate representations are structured around class prototypes defined by final layer weights, having those weights be distributions rather than point estimates should create interesting structural effects in the learned latent space. This could address the overfitting often observed in deterministic layers of Bayesian last-layer architectures, potentially creating internal representations that are naturally better suited for gradient-based interventions—whether for counterfactual generation, model steering, or other forms of latent space optimization.